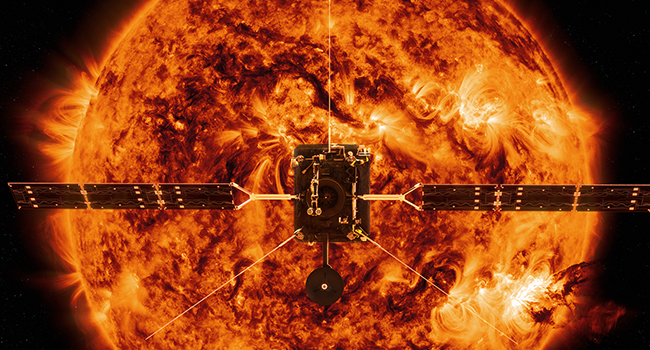

The US-European Solar Orbiter probe launched Sunday night from Florida on a voyage to deepen our understanding of the Sun and how it shapes the space weather that impacts technology back on Earth.

The mission, a collaboration between ESA (the European Space Agency) and NASA, successfully blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral at 11:03pm (0403 GMT Monday) and could last up to nine years or more.

At 12:24am Monday (0524 GMT) the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, received a signal from the spacecraft indicating that its solar panels had successfully deployed.

Space Orbiter is expected to provide unprecedented insights into the Sun’s atmosphere, its winds and its magnetic fields, including how it shapes the heliosphere, the vast swath of space that encompasses our system.

By journeying out of the ecliptic plane — the belt of space roughly aligned with the Sun’s equator, through which the planets orbit — it will acquire the first-ever images of our star’s uncharted polar regions.

Drawing on gravity assists from Earth and Venus, Solar Orbiter will slingshot itself into a bird’s eye view of the Sun’s poles, reaching its primary science orbit in two years’ time.

“I think it was picture perfect, suddenly you really feel like you’re connected to the entire solar system,” said Daniel Muller, ESA project scientist, shortly after the launch.

“You’re here on Earth and you’re launching something that will go close to the Sun.”

“We have one common goal and that is to get the good science out of this mission. I think we’re going to succeed,” added Holly Gilbert, director of NASA’s heliophysics science division.

Space weather

Ten state-of-the-art instruments on board will record myriad observations to help scientists unlock clues about what drives solar winds and flares.

These emit billions of highly charged particles that impact the Earth, producing the spectacular Northern Lights. But they can also disrupt radar systems, radio networks and even, though rarely, render satellites useless.

The largest solar storm on record hit North America in September 1859, knocking out much of the continent’s telegraph network and bathing the skies in an aurora viewable as far away as the Caribbean.

“Imagine if just half of our satellites were destroyed,” said Matthieu Berthomier, a researcher at the Paris-based Plasma Physics Laboratory. “It would be a disaster for mankind.”

Titanium heat shield

At its closest approach, Solar Orbiter will be nearer to the Sun than Mercury, a mere 42 million kilometers (26 million miles) away.

With a custom-designed titanium heat shield, it is built to withstand temperatures as high as 500 Celsius (930 Fahrenheit). Its heat-resistant structure is coated in a thin, black layer of calcium phosphate, a charcoal-like powder that is similar to pigments used in prehistoric cave paintings.

The shield will protect the instruments from extreme particle radiation emitted from solar explosions.

All but one of the spacecraft’s telescopes will peep out through holes in the heat shield that open and close in a carefully orchestrated dance, while other instruments will work behind the shadow of the shield.

Just like Earth, the Sun’s poles are extreme regions quite different from the rest of the body. It is covered in coronal holes, cooler stretches where fast-gushing solar wind originates.

Scientists believe this region could be key to understanding what drives its magnetic activity.

Every 11 years, the Sun’s poles flip: north becoming south and vice versa. Just before this event, solar activity increases, sending powerful bursts of solar material into space.

Solar Orbiter will observe the surface as it explodes and record measurements as the material goes by the spacecraft.

The only spacecraft to previously fly over the Sun’s poles was another joint ESA/NASA venture, the Ulysses, launched in 1990. But it got no closer to the Sun than the Earth is.

“You can’t really get much closer than Solar Orbiter is going and still look at the Sun,” ESA’s Muller said.

Solar Orbiter will use three gravity assists to draw its orbit closer to the Sun: two past Venus in December 2020 and August 2021, and one past Earth in November 2021, leading up to its first close pass by the Sun in 2022.

It will work in concert with NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which launched in 2018 and will fly much closer to the Sun, passing through the star’s inner atmosphere to see how energy flows through its corona.